Innovation Complexity & Transformation Uncertainty

Social scientists are trained to simplify problems by employing Occam’s razor: avoid making models more complicated than necessary. But employing simple linear forecasting breaks down at inflection points, moments when paradigms shift and decisions must be made under heightened uncertainty. At such junctures, it is no longer possible to understand or predict outcomes by simply extrapolating from historical trends. Forecasting in times of radical change requires comprehensive models of socio-economic systems. Complexity analysis begins with the acknowledgement that substantial insight comes from modelling the interaction within and between interconnected systems. Examining systems of systems, whether these are described as multimodal, multilayer or chaotic, has the benefit of treating dependencies between observations as a point of departure rather than as an endogeneity limitation.

The recent award of a Nobel prize to three economists “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth”, highlights the close tie between sustained growth to technological progress. Yet this celebrated model of innovation rests on a paradox, it is built around the notion of “creative destruction”. The central assumption is that existing state of the art acts as a brake to the emergence of transformative innovation. Disruptive innovation would therefore end-up dismantling some industrial sectors. The imagery is of industrial revolutions rising dynamically and emerging as a phoenix from the ashes of old, to forge new paths to value creation. At least in theory.

In this narrative, innovation is portrayed as both a prerequisite and a driving force to the many challenges to industrial transformation. Accepting this perspective is particularly relevant to Europe where industry must transform to meet regulatory steer towards decarbonization. European industry must plan for several interconnected sustainability challenges that include transition to clean energy and circularity in production. And critically, preserve long-term competitiveness in global markets.

And although European R&D investment is outpacing many global competitors, and capital expenditure has remained stable, there is growing scepticism on whether this produces an adequate momentum to achieve a net-zero industrial transformation. With the overall health of the European economy under scrutiny, much hope is placed on innovation as an omnipotent cure. But can innovation serve as the magic wand to deliver economic transformation and sustainable growth? And if it can, under what conditions does it lead to productivity gains that can deliver a substantial comparative advantage?

Beyond competitiveness, the greatest challenge facing Europe’s industrial clusters today is deep uncertainty driven by geopolitical risks and the rapid transformation of trade relations between states. This era of uncertainty is defined by the infamous unknown-unknowns, the risks that cannot be anticipated or quantified.

While industry can navigate and insure against known risks, to which it can assign a probability, pervasive uncertainty is eroding investor confidence and undermines long-term strategic planning. At the same time, companies are struggling to navigate a shifting innovation landscape with rapid industrial transformations to the geography of knowledge capital.

Over the last two decades there has been an exponential growth in the production of IP rights in SE Asia, with Chinese entities now responsible for the majority of new patent filings worldwide. Remarkably, the region’s capacity to generate IP at scale appears to be achieved at a fraction of the cost in other major economies. As demonstrated in the graph below, during 2024 China (9346 patents per $1billion in R&D) has been nearly three times as efficient in converting R&D investment into IP outputs in comparison with South Korea and Japan (3280 patents per $1billion in R&D), who themselves appear to outperform the US by a similar ratio. While patents are an imperfect proxy to innovation, this dynamic amplifies the uncertainty surrounding the future of industrial innovation in Europe and North America. This raises fundamental questions on how to target impactful innovation while addressing potential shortfalls in innovation capacity.

Effectiveness of R&D investment in generating IP

A further dimension of heightened uncertainty is whether the substantial investment in AI, (reported to have exceeded $1.3 trillion between 2020 and 2025 and projected to exceed $7 trillion by 2030), signals a paradigmatic shift. Economists and technologists debate whether we are at the final stage of the information technology wave (i.e. the fifth Kondratieff cycle), with AI seen as an outgrowth of the digital transformation, or alternatively we are at the early stages of a new wave and the beginning of a paradigmatic shift to productivity, which some term a singularity. In the latter case the expectation is that AI will produce industrial transformations by accelerating innovation in many industrial fields such as robotics, biotech and renewables. This of course is further cause for uncertainty as it may dramatically impact industrial efficiency in creating economic value.

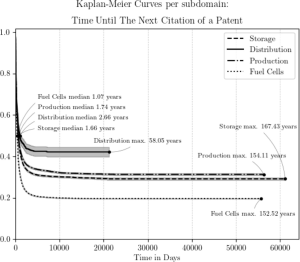

These developments mean that industries operating in an environment of complex innovation are struggling to estimate operational risks, as forecasting becomes uncertain. In work recently published, my team makes a case for looking at the most reliable evidence of invention, the granting of patents. We employ patents that reference previous inventions as a means of predicting the rate of growth in technological frontiers. When there is evidence of a constant rate of development in technology (popularised as Moore’s Law) it is possible to extrapolate from the speed of technological advances in the past to their likely future growth. Our work has taken a further step to use the structure of these references, the citations between patents, to construct a network revealing in depth latent dimensions of the technological frontier within a field. This can be employed to compare competing or synergistic technologies, indicate bottlenecks and to help industry identify where innovation opportunities lie, who owns them and how to navigate this complex landscape. In the table below a survival model predicts the length of time to a citation (i.e. a new patent in the same field) for the four key subdomains of hydrogen technology. Distribution with a long lead time represents a constraint to technological implementation, as confirmed by a number of industry reports.

Radical innovations are by their nature unknown before they are made. A radical invention does not automatically translate to transformative innovation. For example graphene has taken two decades to find market applications. So, regardless of the innovation quotient, patents do not lead to novel ways for creating value until the alignment of associated technological frontiers provide fertile opportunities for their utilisation. It is in the combination and competition between technological frontiers where radical change originates. Our work demonstrates that complexity analysis of patent innovation provide European industry a means to concentrate on quality strategic innovations. By implication, industrial policy can only be effective as part of long-term strategic planning. It has to be attuned to innovation horizons and a drive to enhance intellectual capital. It should be obvious that investing on existing comparative advantage can help to entrench it. It is not as obvious that the biggest opportunities lie between technological frontiers and scientific fields. This calls for supporting multidisciplinarity and lateral thinking in driving innovation. And finally, embracing complexity is critical. Accepting that complex systems cannot be reliably forecast does not mean we cannot map innovation complexity. We can therefore identify technological bottlenecks and innovation opportunities. A robust industrial innovation policy will appraise innovation advantages and disadvantages of existing economic regions to plan beyond extant synergies.

In depth analysis of local innovation systems can reveal the forces that help industrial hubs transcend mere geographic proximity to become engines of collaboration. And to ultimately become the engines of creativity through synergistic internal and external networks. The central challenge is to achieve this transition while fostering the types of innovation that allow economic regions and industrial clusters to sustain their competitive advantage. It is also critical to acknowledge that none of this can occur without active social engagement and broad stakeholder commitment. Innovation never emerges in isolation; it is inherently dependent on the socio-economic institutions that shape and sustain it.

Key points

Radical inventions, such as generative AI, become successful paradigm shifts when multiple technological frontiers align.

Innovation opportunities emerge between shifting technological frontiers, where convergence and recombination create exceptional potential for value creation.

Periods of uncertainty are not only characterized by elevated risk; they also reveal new opportunities and strategic positioning.

Industrial policy during periods of transformation should look beyond traditional competitive advantage and cultivate strategic comparative advantage.

Under heightened uncertainty, decision-making improves by advanced analytic tools capable of modelling multi-level risks, by mapping complexity, and revealing hidden interdependencies.

Acknowledgments

This work has been possible via funding by UKRI through IDRIC, for a project on Knowledge transfer and innovation diffusion. Thanks to my collaborators Kostas Bisiotis, Umit Bititci, David Dekker, Ragnar Gudmundarson, Stefan Koeppl, Heather McGregor, Matthew Smith, Victor Rosenberg, and George Tzougas for their contribution and support.

SELECTED BIBLIO

Bisiotis, K., Christopoulos, D., & Tzougas, G. (2025). Forecasting Carbon Prices: A Literature Review. Journal of Forecasting.

Dekker, D., Christopoulos, D., McGregor, H. (2025). Dynamics of Knowledge Production, Sustainable Futures.

Dickison, M. E., Magnani, M., & Rossi, L. (2016). Multilayer social networks. Cambridge University Press.

Farmer, J. D. (2024). Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World. Yale University Press.

Gillingham, K.T., et al. (2025) New frontiers in research on industrial decarbonization. Science 390,338-340. DOI:10.1126/science.ado2624

IEA (2025), Global Hydrogen Review 2025, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2025.

Knoke, D., Diani, M., Hollway, J., & Christopoulos, D. (2021). Multimodal Political Networks. Cambridge University Press.

Köppl, S., Köppl-Turyna, M., & Christopoulos, D. (2025). The performance of government-backed venture capital investments. Research Policy, 54(8), 105270.

Maslej,N. et al.(2025) “The AI Index 2025 Annual Report” AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, April 2025.

OECD (2025), Measuring Science and Innovation for Sustainable Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3b96cf8c-en.

Segarra-Blasco, A., Tomàs-Porres, J., & Teruel, M. (2025). AI, robots and innovation in European SMEs. Small Business Economics, 1-27.

Smith, M., & Christopoulos, D. (2025). An examination of country participation in carbon capture projects. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 81, 104418.

Smith, M., & Christopoulos, D. (2025). GVC participation and carbon emissions–A network analysis. Ecological Economics, 228, 108450.

DATA